© 2025 London Theatre - The West End Guide. Created for free using WordPress and Kubio

Review: Titus Andronicus

by Mike Matthaiakis

From the moment the lights come up on a stark, tomb-like stage encircled by ominous metal grilles, it’s clear that the Royal Shakespeare Company’s new Titus Andronicus is not just a performance but an experience – one that grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go. Director Max Webster’s vision of Shakespeare’s bloodiest tragedy is as bold as it is precise, crafting a modern nightmare that throbs with timeless anguish. Clad in drab military coats under the cold glow of fluorescent lights, the world of this Titus feels unnervingly familiar: a once-great general and father is welcomed home not to laurels, but to a society teetering on the edge of barbarism. What follows in this five-star production is a masterful tightrope walk between horror and humanity, a staging at once relentlessly brutal and unexpectedly beautiful in its theatricality.

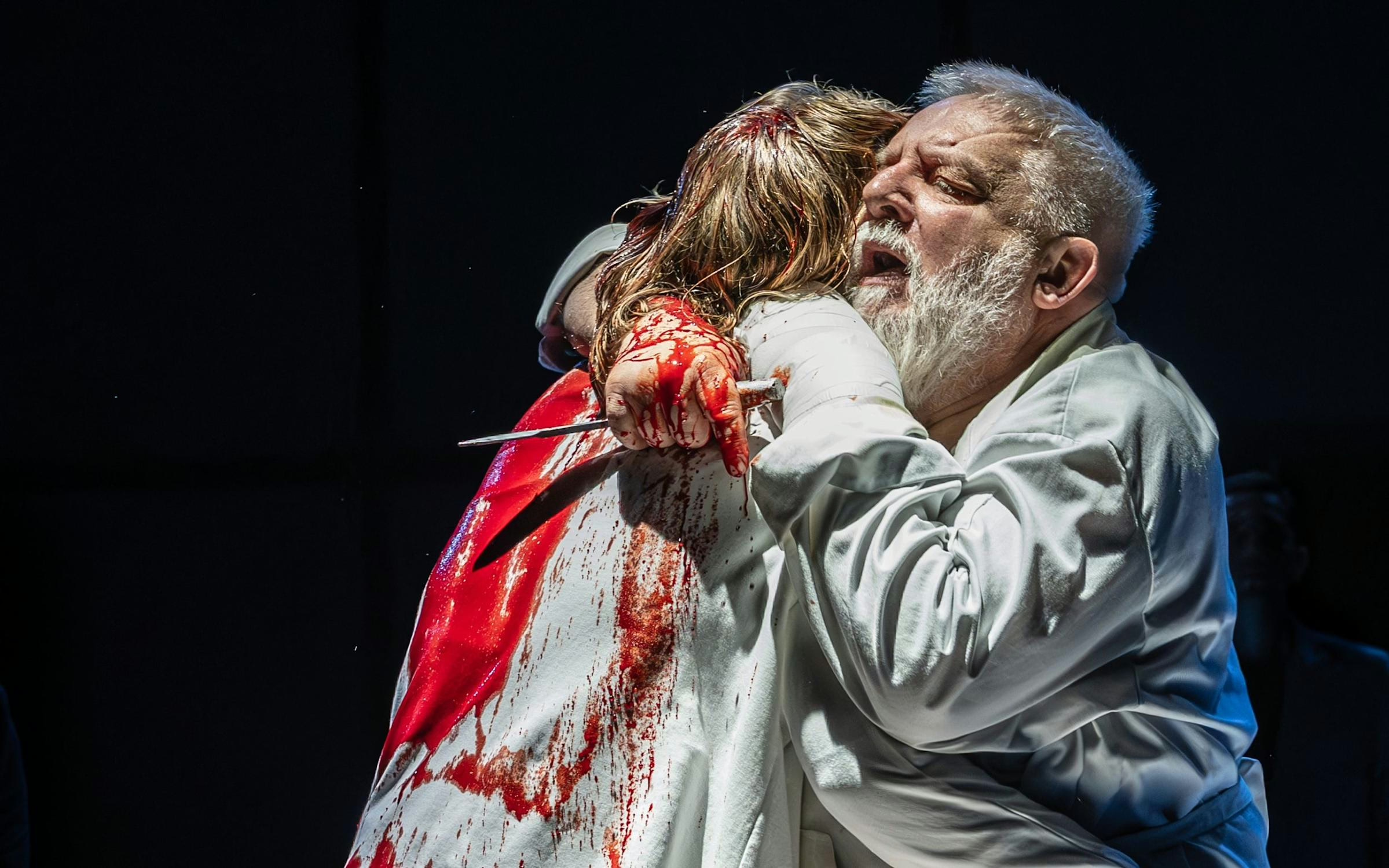

At the production’s core is Simon Russell Beale, delivering a towering performance as Titus that will undoubtedly enter the annals of great Shakespearean portrayals. Beale is a legendary interpreter of the Bard, and here he shows us exactly why. His Titus begins as a weary elder statesman – stooped shoulders bearing the invisible weight of decades of war and the sacrifice of twenty-one sons. There is a heartbreaking authenticity to his early moments of noble restraint; with just a furrow of his brow or a quiet, tremulous inhale, Beale conveys Titus’s sincere hope that duty and honor might still prevail in Rome. Yet as fate cruelly strips everything away from Titus – his position, his remaining children’s lives, and the dignity of his beloved daughter – Beale transforms before our eyes. His Titus cracks and then shatters, shards of grief and madness glinting in his eyes. In one shattering scene, Titus cradles the ravaged Lavinia (played with gut-wrenching fragility by Letty Thomas) in his arms; as he presses his forehead to hers, Beale’s guttural sob – a sound somewhere between a prayer and a howl – moved many in the audience to tears. Minutes later, that same man is plotting unspeakable vengeance with an eerie, chilling calm. The range of emotion Beale unleashes is extraordinary. When Titus feigns madness, capering about in a cook’s apron as he cheerfully bakes pies filled with human flesh, Beale infuses those ghastly comic beats with a sinister glee that is both unsettling and darkly funny. And in the final banquet scene, as Titus delivers his ultimate revenge with a macabre hospitality (“Will’t please you taste of what is cook’d?” he asks with a cordial smile that barely conceals the venom in his voice), Beale’s performance reaches a terrifying zenith. It is a tour-de-force turn – deeply empathetic yet unflinchingly ferocious. Even in the play’s most grotesque moments, Beale finds a tragic soulfulness; he makes Titus’s poetic laments ring clear as bells amid the cacophony of violence. This is Simon Russell Beale at the height of his powers, and he anchors the production with gravitas and gravitating intensity.

Joel MacCormack as Lucius, Simon Russell Beale as Titus Andronicus and Emma Fielding as Marcia Andronicus in Titus Andronicus. © Marc Brenner

Webster surrounds his star with an ensemble that is as strong as any seen on the Swan Theatre stage in recent memory. In this adaptation, Titus’s stalwart brother Marcus is re-imagined as Marcia, an inspired change that yields poignant results. As Marcia, Emma Fielding exudes a quiet authority and compassion; she shares a sibling chemistry with Beale that feels lived-in and true. Fielding’s performance is a subtle standout – watch her face during Lavinia’s trauma or her body language as she supports Titus’s shaky frame in moments of despair. Marcia becomes the emotional backbone of the Andronicus family, and Fielding’s understated resolve speaks volumes about endurance and loyalty. Letty Thomas, as the ill-fated Lavinia, delivers one of the evening’s most wrenching portrayals despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that her character’s tongue is cut out halfway through the play. Thomas’s wide, expressive eyes and piteous, animal-like cries convey Lavinia’s unspeakable pain more eloquently than any monologue could. Her silent scream upon being presented to her uncle and father after the assault is a moment that will be seared into my memory – an image of pure horror and innocence destroyed. It’s to Thomas’s great credit that Lavinia’s suffering never feels sensationalized; she elicits our deepest pity and respect, never mere disgust.

Marlowe Chan-Reeves as Chiron, Natey Jones as Aaron and Jeremy Ang Jones as Demetrius in Titus Andronicus. © Marc Brenner

On the opposite end of the moral spectrum, Natey Jones is a revelation as Aaron the Moor, one of Shakespeare’s most unapologetic villains. Jones plays Aaron with a charismatic swagger and simmering rage – he often prowls at the edge of scenes, a predator biding his time. When plotting evil, his Aaron is gleefully wicked, flashing a lupine grin at the audience as if inviting us to revel in his mischief. But Jones also allows flickers of humanity to pierce through Aaron’s villainy. In a brilliantly staged twist, when Aaron discovers he has fathered a baby boy (a rare moment where the character’s guard drops), Jones delivers a fierce plea for his child’s life that momentarily wins our sympathy. It’s a complex performance that adds layers to a role often played as purely demonic. As Aaron’s partner-in-crime, Wendy Kweh makes a ferocious Tamora, the Goth queen-turned-empress hell-bent on revenge. Kweh’s Tamora is equal parts regal and ruthless – one moment seductively purring words of deception, the next moment baring her teeth in a primal scream of vengeance. She captures Tamora’s transition from grieving mother to remorseless avenger with exhilarating bravado. Tamora’s sons (played with obnoxious brio by Jeremy Ang Jones as Demetrius and Marlowe Chan-Reeves as Chiron) are suitably loathsome, each eager to one-up the other in cruelty, which makes their ultimate comeuppance at Titus’s hands all the more darkly satisfying. Joshua James embodies Emperor Saturninus with a sleazy, cowardly charm – he’s the spoiled man-child of the piece, and James’s performance deftly shows how this capricious tyrant’s insecurity and vanity fuel the spiral of violence. Completing the cast, Joel MacCormack brings a steely composure and moral clarity to Lucius, the last upright Andronicus. His performance is quietly commanding – a figure forged in war but tempered by grief, who must carry forward the flickering torch of justice after the carnage. In contrast, Tristan Arthur as Young Lucius provides one of the production’s most haunting moments. His clear, delicate solo – a Latin hymn sung amidst the shadows – offers a fleeting innocence that starkly contrasts the bloodied world around him. It’s a devastating reminder of what is lost with each act of revenge. Ned Costello, portraying both Bassianus and Publius, brings a cool-headed dignity to his roles, offering much-needed stability amidst the swirling chaos of Rome. As Bassianus, the noble brother of the emperor, Costello carries himself with a quiet conviction that makes his early demise all the more tragic – his presence lingers in the play like a ghost of what Rome might have been under steadier hands. In his later scenes as Publius, Costello shifts registers with finesse, bringing a sense of procedural calm and duty as the machinery of justice grinds toward its grisly conclusion. It’s a testament to Costello’s clarity and control that even in supporting roles, he makes a lasting impact.

If the actors provide the heartbeat, Max Webster’s direction and the production design supply the lifeblood – quite literally. This Titus Andronicus is awash in blood, as it must be, but Webster stages the violence in ways that are consistently inventive and thought-provoking rather than merely shock-inducing. Joanna Scotcher’s set presents a grey, dystopian Rome that visually prepares us for a story of moral decay. The stage floor is a pale, marbled surface with a subtle trench around its perimeter – which, we soon realize, functions as a discreet blood gutter. (Indeed, by play’s end, that trench runs red.) Looming at the back are tall frosted-glass doors and a wall of soft-lit memorial candles, suggesting both a mausoleum and a modern chapel – an altar to the play’s many victims. This elegant minimalism means that when the gore arrives, it pops against the canvas of grey. And arrive it does: Webster does not shy away from Titus’s notoriously gruesome set-pieces, but he stages them with a theatrical flair that had the audience alternately wincing and marveling. The violence is often choreographed in stylized tableaux that highlight the ritualistic nature of revenge. For example, the execution of Tamora’s son Alarbus early in the play is done offstage, but we see a splash of red spray across a translucent screen and hear the chilling snick-snack of a blade – an opening salvo that primes our imagination. Later, when Lavinia is attacked in the forest, the director employs a kind of symbolic dance: the actress is lifted and contorted by the predatory brothers in a horrifying ballet, while the lights strobe and a cacophony of howls and drums (part of Tingying Dong’s visceral sound design) assault our ears. It’s mercifully brief, but utterly harrowing.

Letty Thomas as Lavinia in Titus Andronicus. © Marc Brenner

Webster also finds grisly humor in creative staging. Each subsequent atrocity seems to be accompanied by a “how will they do it?” anticipation. A particularly striking device is the use of overhead mechanized tracks – at times the stage resembles an abattoir, with steel hooks lowering from above to carry off bodies or body parts. When Titus’s sons are executed offstage, a severed hand (one of Titus’s, given in vain to ransom them) is dropped onto the stage from those rafters with a sickening thud – prompting a collective gasp, followed by a few nervous chuckles when a character drily comments on it. In perhaps the most startling Grand Guignol moment, a buzzing chainsaw makes an appearance (a clever modern substitution for Titus’s sword): one character’s hand is sawed off in full view, but the act is rendered in silhouette against blinding sparks and a high-pitched keening sound, more suggestive than explicit. By the time Titus and his family don plastic ponchos to slaughter Tamora’s sons like livestock, the production has primed us to accept these horrors as part of its twisted language. There is an operatic, over-the-top quality to the gore – a sense that we are witnessing a savage ritual or nightmare, rather than literal violence. This choice smartly prevents the audience from disengaging; instead of averting our eyes in disgust, we lean in, horrified yet captivated by the theatrical daring on display. Credit must also go to Lee Curran’s lighting, which works in tandem with the staging to control what we see (and what we think we see). Quick blackouts and flickers serve as merciful blinks during the most brutal slayings, leaving just enough to the imagination. Meanwhile, Curran bathes the aftermath of each bloodbath in cold white light or sometimes an eerie red glow, as if illuminating the moral stains left behind. The cumulative effect is immersive and unsettling: by the end of the performance, one feels almost complicit in the cycle of revenge, having been seduced by the spectacle and then confronted with its human cost.

Amid all this darkness, Webster shrewdly threads moments of black comedy that the cast seizes with aplomb. Titus’s feigned madness brings several grim laughs – Beale’s deadpan delivery when Titus sends his own hand as a “gift” to the emperor got an incredulous guffaw from the audience. And in the notorious final scene, as the characters unwittingly dine on meat pies baked from Tamora’s sons, the grotesque humor had people alternately cackling and covering their mouths. It’s a daring tonal shift, but it works, in large part because the production has built up to it and earned it. By allowing us to laugh at the absurdity of the bloodshed (just for a moment), Webster underscores one of the play’s central ironies: the cycle of revenge is both terrifying and tragically futile, a savage joke played by history over and over.

In the final minutes, as bodies lie strewn and the few survivors stumble offstage, a hush fell over the Swan Theatre. The young Lucius, now an orphaned boy poised to inherit this broken world, gingerly steps forward and sings a brief requiem – the same pure notes we heard at the start, now fraught with sorrow. It’s an ending that left the audience breathless, sitting in stunned silence before erupting into a standing ovation. Max Webster’s production of Titus Andronicus is a triumph on every level. It takes one of Shakespeare’s most challenging, grim texts and delivers it with clarity, creativity, and an unflinching emotional truth. The performances are universally superb, led by Simon Russell Beale’s once-in-a-generation Titus. The staging manages to be both slickly modern and faithful to the primal spirit of the play. And above all, it packs an emotional wallop – by the curtain call, we are equal parts drained and exhilarated, reminded of theatre’s unique power to confront us with the worst of humanity while also illuminating our capacity for endurance, loyalty, and even forgiveness. This Titus Andronicus is not for the faint of heart, but those who brave its bloody depths will find rich rewards. In Webster’s hands, Shakespeare’s early revenge tragedy becomes more than a catalog of horrors; it’s a haunting reflection on grief, justice, and the corrosive allure of vengeance that speaks potently to our times.

A visceral, unmissable revival. The RSC has delivered one of the definitive Titus Andronicus of our era, a production as thrilling as it is profound. Whether you’re a Shakespeare devotee or a newcomer, consider this an essential theatrical feast (just maybe don’t eat the pie!). We hope to see this in London once it completes its run at the Swan Theatre.

“Titus Andronicus” is running until 9 June at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-Upon-Avon

Read reviews and book tickets in the cheapest way possible.

© 2025 London Theatre - The West End Guide. Created for free using WordPress and Kubio